During the pre-settlement period, the man was a hunter, collector of food, and experimenter with nature. Later, he learned to domesticate animals and plants and started settling permanently and growing crops. Domesticated many food crops, and learned to store for future use which can be witnessed in the Indus Valley civilization. Before the colonial period, many local communities were involved in shifting cultivation and traditional agroforestry systems without any restriction from anyone.

Later, the British influenced what to grow and how much to grow (Tinkathia system) and how to grow (by easily converting forest land into cropland for high tax generation). This was a major shock to farmers, especially nomadic people who depended on forestry and shifting cultivation for their survival. They restricted them to settling in one place for ease of collection of taxes and forced them to cultivate particular crops. Gradually, this traditional farming practice is changed into a permanent practice. Many people think it is an unsustainable practice, causes deforestation, and reduces soil fertility. Let’s discuss all the shifting cultivation systems practiced in many parts of India and draw a conclusion to our question: Is shifting cultivation sustainable?

It is also known as Jhum (Slash and Burn) cultivation, a primitive agricultural practice followed by indigenous communities. In this system, natural vegetation is cleared, burned except for a few important vegetation, and cropped with crops for a few years, and then left unattended for fallow. In the traditional system, the land was left fallow for more than 20 years, which gives sufficient time for the regeneration of natural vegetation. This practice consists of cutting off a patch of forest trees before the onset of monsoon, burning the debris in situ shortly before the first rains, and sowing crops, such as maize, rice, beans, cassava, yams, and other vegetables.

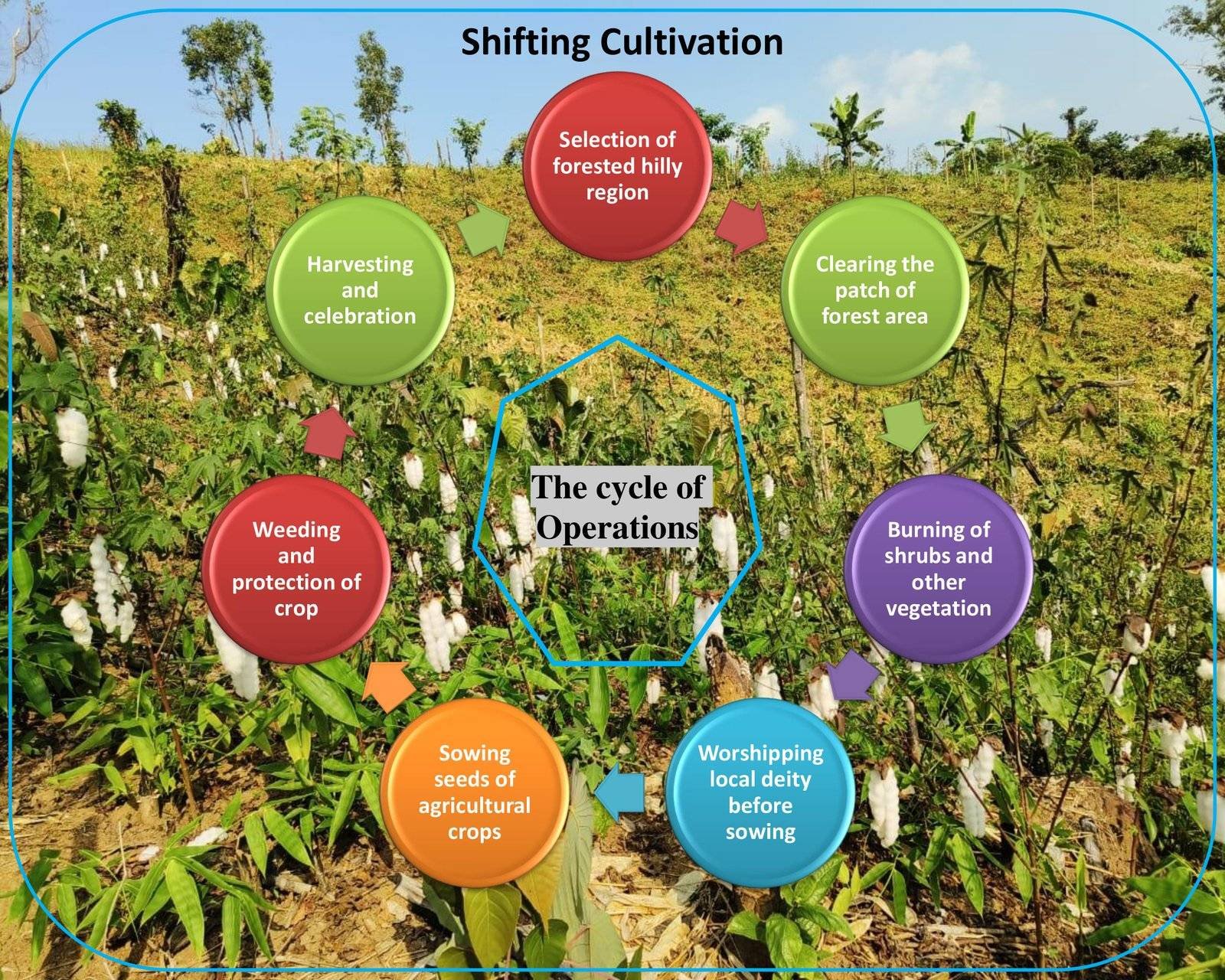

The main features of this system are intercultural operation by manual weeding and irregular patterns of intercropping. After 2-3 years of cropping, the field is abandoned and left to fallow for 10-20 years for the land rejuvenation. Then, farmers or communities return to the same field after a fallow phase of 10-20 years, clear the land once again and the cultivation cycle is repeated. This period has now reduced to 5-6 years due to increased population, This created negative effects on ecological balance causing yield reduction and food insecurity. The cycle of Jhuming operations in all the North Eastern states is illustrated in the below figure.

The cultural norms, values, beliefs, and rituals also form an inseparable part of this knowledge. Indigenous knowledge, encompassing land management, biodiversity conservation, water management, health care, and medicines, is developed through generations of observation and experimentation, transmitted orally or through experiential learning. The length of the fallow period is critical in determining the success and sustainability of the practice. Long fallow periods were a feature of traditional shifting cultivation, which is a rather effective technique for managing soil and is well suited to the local ecological and socio-cultural circumstances.

A long fallow period allows storage of nutrients in the biomass and topsoil, which creates a closed nutrient cycle of constant transfer of nutrients from one compartment of the system to another through various biophysical processes of rainwash, litterfall, root decomposition, and plant uptake. However, increased demand for food, reduced land holding size, and intensive agriculture reduced the fallow period, which resulted in soil erosion, and fertility loss and became unsustainable.

Despite the remarkable similarity in Jhum cultivation practiced in the country, minor differences exist and often depend upon the environmental and socio-cultural conditions of the region and the historical features that have influenced the evolution of the land use system over the centuries (Nair, 1993). These variations are reflected in various names in different parts of the country. Shifting cultivation is practiced in North Eastern states, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Orissa.

The cultivation practice is more or less the same in different parts but the names of this practice are different in different parts of the country. In North East India, shifting cultivation is called ‘Jhum’while in South India known as Podu and Kumari. However, in many tribal communities in central and South India, it bears different names. Several ethnic groups that practice shifting cultivation in different parts of India are listed in Table, along with the area, the major crops, and the tree species composition.

Different names of Shifting cultivation practices in India

| Name | State | Ethnic group | Crops |

| Bari system | Central India (Madhya Pradesh) | Gond | Food crops: Rice, Wheat, Millet, Pulses, and vegetables Bio-fencing crops: Lantana, Mehndi, andNirgundiTrees: Mahua, Tendu, Neem, etc. |

| Bewar system | Central India | Baiga | Food crops: Millets, pulses, and vegetables Trees: Kusum, Mahua, Neem, Vitex, etc. |

| Jhum cultivation | North Eastern India | Most of the primitive ethnic communities | Food crops: Rice, Maize, Millets and vegetablesCash crops: Ginger, Turmeric, Pineapple, Jute, Pineapple, Oranges, etc. |

| Kumari cultivation | Karnataka | Betta Kuruba, Jenukuruba, Malekudia, and Soliga | Food crops: Ragi, tubers, vegetablesFruit crops: Jackfruit, Lemon, Mango, Banana, Papaya |

| Podu cultivation | Andhra Pradesh | Koyas, Kondareddis, Kondhs, etc. | Food crops: Ragi and other millets, maize, pulses, and vegetables. |

| Odisha | Bondo, Didayi, Koya, Gadaba, Paroja, Soura, Kondha, Juang, Parenga, Paudi Bhuyan, and Erenga Kolha | Food crops: Millets, pulses, tubers, turmeric, etc.Trees: Mahua, Mango, Tamarind, and Palmyra. |

- Bari System (Central India)

This type of agroforestry system is practiced by the Gond community, which is dominant in Madhya Pradesh. This Indigenous community grows various crops: rice, wheat, maize, pulses, and oilseeds in Kharif and Rabi seasons in mixed farming along with some bio-fencing crops such as mehndi (Lawsonia inermis), lantana (Lantana camara), and nirgundi (Vitex negundo), and trees like Mahua (Madhuca longifolia), Tendu (Diospyros melanoxylon), Neem (Azadirachta indica), etc.

The Mahua tree has cultural significance as it is used to offer a cup of ‘mahua liquor’ to their local deity during the first sowing of the year and before weddings. Local people also believed that fixing a branch of bhilwa (Semecarpus anacardium) in the crop field on the day of the lunar eclipse eradicates and wards off such insects. They use this traditional belief as an insecticide. Hence, the trees in this traditional agroforestry system are deeply rooted in their culture. This system also provides food and income and supports biodiversity and soil health.

- Bewar system (Central India)

This traditional agroforestry system is a shifting slash-and-burn method of growing crops practiced by the baiga community. They grow a variety of crops such as millets (sikia, kang, kutki, sawa, mandiya, degra, jhurga, jhujhru), pulses (Black Gram, mung, bedra, salar), and vegetables like lauki (gourds) and cucumber. There will be three patches of bewar land, of which two were kept fallow each year, with cultivation alternating among them. People conserve some trees and they don’t cut them due to their economic significance: kusum, mahua, and any other useful tree. A mixed crop of millets, pulses, and oilseeds grown in the uplands and medium lands is one traditional practice that will increase resilience in the context of climate uncertainties. The leaves of Neem and Vitex are used as biopesticides as insect and pest repellents.

- Jhum Cultivation (North Eastern India)

Jhuming is the dominant farming practice in North Eastern India. Nagaland has the highest area under Jhum cultivation followed by Manipur, Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, and Mizoram. This practice is characterized by clearing and slashing fertile forest area, generally less than 1.5-2.0 ha followed by burning the natural vegetation and tillage before the cultivation phase. The cultivation phase involves mixed cropping involving soil-exhausting crops like rice, maize, millets, and cotton, and soil-enriching crops like legumes are grown together and cropped for 2-3 years.

Traditionally, jhumias grew only food grains and vegetables, however, nowadays most communities have shifted to cash crops such as ginger, turmeric, pineapple, jute, etc. Among food grains, rice, maize, millets, and pulses are dominant, among vegetables a variety of legumes, potato, pumpkin, cucumbers, yams, tapioca, chilies, beans, onion, and arum are cultivated. Ginger, linseed, rapeseed, upland sesame, oranges, and pineapples are important cash crops grown by Jhumias to sell in the weekly market.

Further reading: https://doi.org/10.56405/dngcrj.2017.02.01.07

- Kumari cultivation (Karnataka)

Shifting cultivation in Karnataka is practiced by the Betta Kuruba, Jenukuruba, Kuman, Kurnbi, Malakudia, Marati, and Soliga tribes. The methods followed in shifting cultivation are almost the same as ‘Podu’ cultivation with some different crops. Before sowing, ceremonies would be performed to the ‘Bhumi tayi’ (Goddess of the earth). During the onset of the monsoon, they plant traditional bananas, chilies, papaya, guava, jackfruit, acid lime, and lemon. This Soliga tribe is also involved in biodiversity conservation as they move from one land to another, they leave grown crops (Banana, tubers, mustard, amaranthus, ragi, papaya, tapioca, bottle gourd, cucumbers, pumpkins, climber beans, lemon, and jackfruit) as it is in the land, which is the food for wild boar, deers, ants, parrots, doves, insects, etc. They also dug pits or wells, wherever they practiced shifting cultivation which would be a source of water for animals after they moved away.

- Podu Cultivation

5.1. Andhra Pradesh: Shifting cultivation is practiced in tribal dominant areas like Srikakulam, Vizianagaram, Visakhapatnam, and East Godavari districts with different names by different ethnic groups; tribes in the northern coastal area call it ‘Podu’; Gonds and Kolams of Adilabad ‘Padaka’ and ‘Vagad’ respectively, whereas Koya call it ‘Lankapadsenad’. There are two types of ‘Podu’ in practice, namely ‘ Chelaka Podu’ (practice in plain areas) and ‘Konda Podu’ (practice in hilly areas). Indigenous tribes like the Koyas, Kondareddis, Kondhs, etc. are very careful in choosing the location for ‘Podu’ by using their traditional knowledge. According to them, the species of trees, shrubs, and bushes with thick leaves indicate the higher fertility of Podu land. While selecting a site, cultivators consider not only the physical attributes of the land but also its distance from their habitats.

After the selection of land for ‘Podu’, the tribes start clearing natural vegetation on an auspicious day in consultation with ‘Dasari’ or ‘Muhurtha Gadu’ (local priest) before the onset of monsoon (in summer), they offer a fowl and coconut to the local deity. In April, they burn the dried bushes and spread the ashes into the soil in May. During the onset of monsoon in June, dribbling or broadcasting of seeds of maize, rice, castor, ginger, millets, especially Ragi (Finger millet), Sama (Little millet), Granti (Pearl millet), Korralu (Italian millet) and Jonnalu (Jowar), and pulses like red gram, black gram, green gram is followed. In July and August, they take care of crops against wild animals, birds and pests, and occasional weeding is done. Harvest starts in September and continues till December. Thereafter, harvest various crops like maize in September, millets in October, Jowar in November, and Ragi in December. This completes the one cycle of shifting cultivation / ‘Podu’. Harvested crops are stored in bamboo baskets for future use.

5.2. Odisha: Whereas in Odisha, this cultivation is practiced by various tribes like Bondo, Didayi, Koya, Gadaba, Paroja, Soura, Kutia Kondha, Dongaria Kondha, Kandha, Parenga, Jatapur, Juang, Paudi Bhuyan, and Erenga Kolha. They grow a variety of crops like finger millet, foxtail millet, little millet, kidney beans, turmeric, red gram, green gram, and some tubers. In March-April, the community collaborates to locate land within the village boundaries, clear small thorny shrubs, and subsequently fell small trees, excluding mango, tamarind, mahua, and palmyra (utilized for country liquor production). After a month of drying, a portion of the logs is reserved for constructing temporary hutments in the shifting fields, while the remainder is burned. Half of the unburned wood is then gathered for fencing purposes. In the initial years of cultivation in a shifting field, finger millet is the primary crop alongside a mix of other crops and kandula (a type of pulse), forming a diverse cropping cycle that addresses alternative food needs from August to February.

A short cultivation phase (1-3 years) with a long fallow period (15-20 years) seems to be sustainable. Traditional shifting cultivation was an Indigenous knowledge-based production system that aids in maintaining the traditional culture and heritage of the Indigenous people. This system maintains agrobiodiversity with many seasonal crops like rice, vegetables, and fruits, which provide food at least for a few months of the year. Apart from slashing and burning, it follows subsistence organic farming with zero tillage cultivation system with minimum soil disturbance and nutrient loss. This is a rainfed agriculture practice, so no need for watering or irrigation, no external inputs are required, and hence, the cost of cultivation is almost nil. Jumias have their own preserved seed for future cultivation. Jhum cultivation is a major source of livelihood for many tribal groups in hilly regions.

Some proponents of shifting cultivation claim that it has advantages over monocropping and conventional agriculture. It does not use fertilizers or chemical pesticides to force crops to grow in nutrient-depleted soil it increases some nutrients slightly (potassium, phosphorus and organic matter) in the soil (Nair, 1993). Jhum crops are the result of many trials and errors and vast experiences and observations. They are highly resistant to pests and diseases and have high genetic variations able to adapt to various climatic conditions. Mixed cropping with some culturally important trees ( which are left undisturbed during slashing and burning) acts as insurance against changing climate and environmental shocks. In addition, Crop diversity is the major advantage of Jhum cultivation, it has a great significance in food and nutritional security. It offers many local fruits, vegetables, and spices on a small piece of land. Hence, people do not need to worry about their food and vegetables for their daily needs.

Demerits of Shifting Cultivation

The slashing of natural vegetation or tree cover in hilly areas with short fallow periods causes habitat loss for wildlife, soil erosion, and soil degradation. Every year, thousands of hectares of forest are destroyed due to shifting cultivation, which is causing changes in the forest ecosystem. Though shifting cultivation has many advantages, its first phase of slashing and burning is the major drawback which makes shifting cultivation an unsustainable practice. The major negative impacts on the environment are soil health and changes in the forest ecosystem.

Clearing and burning the forest land leads to disruption of the closed nutrient cycle. During burning operation, soil temperature increases, and direct solar radiation on bare soil results in higher soil and air temperature, which causes changes in the physical and biological activity of soil. It accelerates soil erosion manifold. Burning causes air pollution, fear of forest fire, and loss of soil nutrients and useful soil fauna and flora. Most shifting cultivation is subsistence in nature, low input and output ratio compared to other farming systems/ methods. Intensive agriculture practice with lower inputs not only causes soil fertility depletion but also converts primary forest land into secondary woodland of shrubs. In the phase of soil property, it increased the soil and gully erosion and acidification.

Deforestation by shifting cultivation leads to the loss of natural forest ecosystems creating a huge impact on the environment. Loss in forest cover results in climatic variations in rainfall, temperature, wind, humidity, etc., and reduces carbon sink. The mass destruction of forest cover with forest canopy gaps leads to deforestation which interferes with the hydrological cycle due to low evapotranspiration.

Another major disadvantage of shifting cultivation is the land can produce crops only once in several years ( 5-19 years) depending on the Jhum cycle. Under settled conditions with some scientific farming methods land can be cultivated every year, which can increase food security and livelihood opportunities for locals. Thus productivity per acre or ha under Jhum is lower than the settled cultivation. The income from Jhum cultivation is very poor compared to prevailing wage rates.

Efforts made to control shifting cultivation in North East

Most development planners and policymakers perceive shifting cultivation as subsistence, economically unviable, and environmentally destructive, and therefore a major problem for the development of states where shifting cultivation is practiced. Governments have consistently tried to replace the practice with settled agriculture, allocating financial outlays to support this transformation. Hence, various Jhum and jhumia rehabilitation schemes have been implemented by the state and Central government since independence to curb shifting cultivation, such as watershed development schemes in shifting cultivation areas (Union Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare), Soil conservation schemes, Jhumia rehabilitation schemes (Government of Tripura), and the New land use policy scheme ( Government of Mizoram).

However, effective implementation of these schemes failed due to a lack of coordination, a top-down approach, direct implementation without checking in pilot projects mode, popularization of high-value cash crops, poor research backup, etc. Despite government efforts and the desire of the community to change, shifting cultivation remains a problem and persists in large parts of the country.

Further reading: http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28006.83522

Amalgamation of shifting cultivation and scientific management

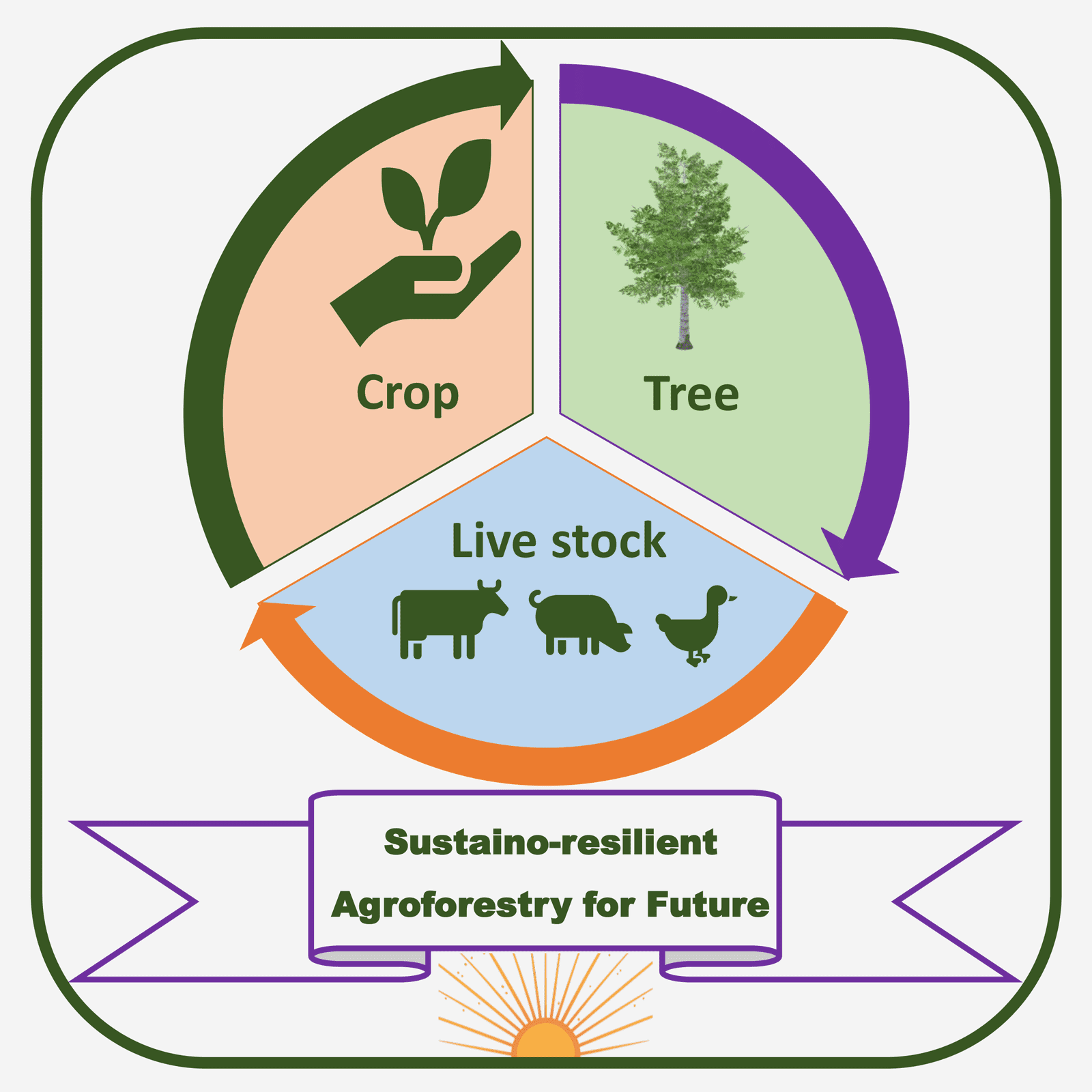

The defect of shifting cultivation lies with deforestation, soil fertility loss, low income, and land rotation with lower inputs. The amalgamation of traditional knowledge with scientific management in settled cultivation can help to conserve traditional, rich knowledge and cause less harm to the environment. Settled cultivation reduces deforestation, land rotation, and changes in the forest ecosystem. The use of climate-resilient local food crops, vegetables, and short-rotation multipurpose perennials with definite row patterns, along with livestock, helps to withstand the changing climate.

Some scientific management practices, like the use of biocontrol agents, biofertilizers, crop rotation, mulching, and manure, help to improve soil health and microbial activity and, as a result, increase soil productivity without causing any harm to the environment. It can increase the income of the ethnic communities and food security, and reduce poverty. Therefore, policymakers should consider these things in mind while making any policies regarding shifting cultivation without affecting their social, cultural, and religious beliefs. As per the Indian State Forest Report 2021, Forests in hills are increasing but decreasing in tribal districts. Hence, proper policy interventions are needed to popularize and strengthen farming practices.

Trending blog: https://whereagroforestrymeetsagriculture.com/industrial-agroforestry/

References

Akter, R., Hasan, M.K., Kabir, K.H., Darr, D. and Roshni, N.A., 2022. Agroforestry systems and their impact on livelihood improvement of tribal farmers in a tropical moist deciduous forest in Bangladesh. Trees, Forests and People, 9, p.100315.

Bhutia, P. L., Bhutia, K. G., Panwar, P., Singh, N. R., Pal, S., & Khola, O. P. S. (2025). Traditional Agroforestry Systems of North-Eastern India: An Overview. Sustainable Management and Conservation of Environmental Resources in India, 2025, 207-234.

Bundela, D. S. 2007. Water Management in Northeast India – Some Case Studies. Edited by Kaledhonkar et al. CSSRI, Karnal. p. 40-46

Deb, S., Arunachalam, A. and Das, A.K., 2009. Indigenous knowledge of Nyishi tribes on traditional agroforestry systems.

Dinesha, S., Raj, A., Bhanusree, M. R., Balraju, W., Rakesh, S., Raj, W. G., Jha, R. K., Neeraj, ., & Kumar, K. (2022). Agroforestry Assisted Natural Farming in India: Challenges and Implications for Diversification and Restoration of Agroecosystem. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change, 12(12), 1053–1069.

Giri, K., Mishra, G., Jayaraj, R. S. C., & Tsopoe, M. (2024). Agrobiodiversity and Crop Productivity of the Alder-Based Jhum Farming System in Khonoma Village, Nagaland, India. In Shifting Cultivation Systems (pp. 65-71). Springer, Cham.

Kaushik, N., Arya, S., Yadav, P. K., Bhrdwaj, K. K., & Gaur, R. K. (2020). Khejri (Prosopis cineraria L. Druce) based agroforestry systems in the arid and semi-arid region: supporting ecosystem services. Indian Journal of Agroforestry, 23(2).