Background

During the pre-settlement period, the man was a hunter, collector of food, and experimenter with nature. Later, he learned to domesticate animals and plants and started settling permanently and growing crops. Domesticated many food crops, and learned to store for future use which can be witnessed in the Indus Valley civilization. Before the colonial period, many local communities were involved in shifting cultivation and traditional agroforestry systems without any restriction from anyone. Later, the British influenced what to grow and how much to grow (Tinkathia system) and how to grow (by easily converting forest land into cropland for high tax generation). This was a major shock to farmers, especially nomadic people who depended on forestry and shifting cultivation for their survival. They restricted them to settling in one place for ease of collection of taxes and forced them to cultivate particular crops which are less viable to cultivators. It pushed the indigenous people to further poverty.

During post-independence, increased population, famine situations, food insecurity, and dependence on food grain imports paved the way for the Green Revolution. Though it seems to have played an important role in food security, it left many scars on Mother Earth due to its unsustainability. After all these restrictions and the green revolution, traditional agroforestry systems are still prevalent in some parts of India and the world due to ethnic communities. Thanks to their contributions to preserving rich culture by conserving indigenous trees and crops through their traditional agroforestry practices.

This work discusses the role of tribals and other Indigenous communities in agroforestry practices and the conservation of many species. Here, our main focus is on the indigenous agroforestry systems that have originated from the Indian subcontinent after trials and errors of indigenous knowledge and innovation over the centuries.

What is Indigenous Agroforestry?

Indigenous agroforestry (IAF) is agroforestry that has long been practiced by indigenous communities within the context of their traditional agriculture systems. Historically, it precedes experimental agroforestry or modern agroforestry which is practiced by research scientists and research going on suitable models to different geographical areas. Whereas, indigenous or traditional agroforestry systems are practiced in real life, ongoing enterprises within or adjustment to farmer’s fields. Traditional agroforestry system has a long history, which is developed after long observations and experiences, local requirements, and their cultural importance. This rich traditional knowledge is transferred from one generation to another generation from their elders. This indigenous knowledge is based on agrobiodiversity, which is crucial for food security. The indigenous population’s relationship with nature symbolizes a higher connection with religiosity; their practices represent the conservation of biodiversity, and such practices must be reclaimed since they correspond to ways to reduce food and socio-environmental impacts.

Shifting Cultivation / Slash and Burn Cultivation: A Primitive Cultivation Practice

It is also known as Jhum cultivation, a primitive agricultural practice followed by indigenous communities. In this system, natural vegetation is cleared, burned except few important vegetation, and cropped with crops for a few years, and then left unintended for fallow. In the traditional system, the land was left fallow for more than 20 years, which gives sufficient time for the regeneration of natural vegetation. This practice consists of cutting off a patch of forest trees before the onset of monsoon, burning the debris in situ shortly before the first rains, and sowing crops, such as maize, rice, beans, cassava, yams, and other vegetables. The main features of this system are intercultural operation by manual weeding and irregular patterns of intercropping. After 2-3 years of cropping, the field is abandoned and left to follow for 10-20 years for the land rejuvenation. Then, farmers or communities return to the same field after a fallow phase of 10-20 years, clear the land once again and the cultivation cycle is repeated. This period has now reduced to 5-6 years due to increased population, This created negative effects on ecological balance causing yield reduction and food insecurity.

Prominent Indigenous Agroforestry Practices for Sustainable Land Use Management

Earlier people with conservation ethos knew how to live a happy and sustainable life. Indigenous people are inseparable from nature and its surroundings as they worship trees, bushes, and animals that dwell in the forests as totems and believe that their gods and ancestors’ spirits reside in the forest. So, they never want to deplete it but conserve it through their traditional conservative methods. Our forefathers knew what is replenishing and what is permanently depleting. Hence, Though their knowledge, community engagements, and practices gave some important messages, rituals, and roles for conservation and continuation through their ethos for instance bishnois 29 principles from northern India to Soliga aboriginals in southern India ultimately speaks about simple life, living in harmony with nature, and nature is everything. Indigenous communities through their observations and experiences found some prominent traditional agroforestry systems. The following systems are some examples of traditional agroforestry systems or Indigenous agroforestry methods.

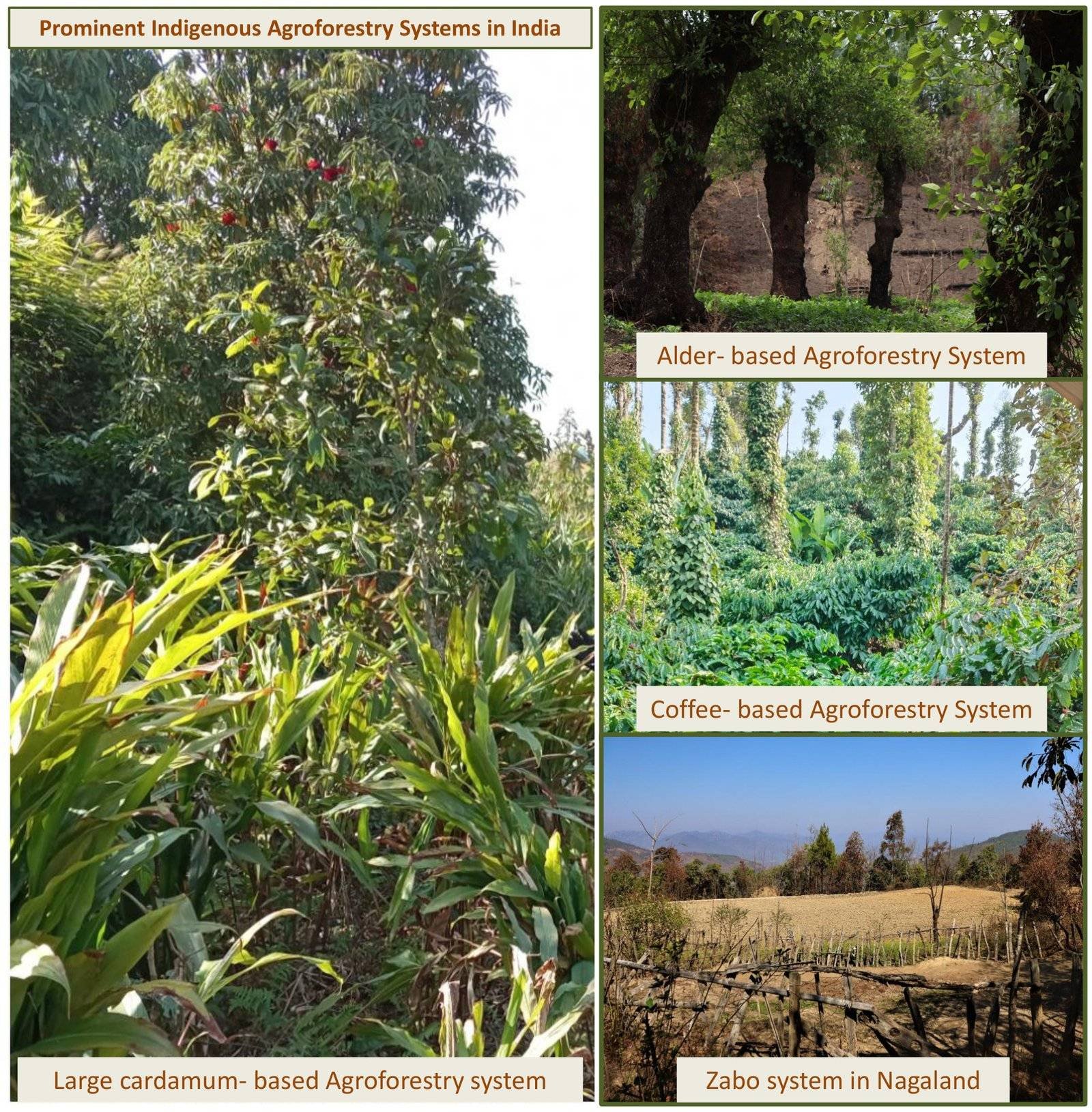

Prominent Indigenous Agroforestry Practices in India

| Name of AFS | State | Crop component | Trees or Perennials | Animal or Livestock | Benefits | Reference |

| Alder-based Agroforestry System | Nagaland (Angami, Sumi, and Konyak practice) | Rice, maize, colocasia, vegetables, tapioca | Alder | – | Innovative soil management practice. | Giri et al., 2024 |

| Bamboo and Pine Homestead Agroforestry | Arunachal Pradesh (Apatani tribe in Ziro valley) | – | P. bambusoides and P. wallichiana are highly preferred bamboo and pine species | – | Aid in diverse agro ecological services and improving agrotourism. | Taka and Tangjang, 2015 |

| Native tree-based Coffee Agroforestry | Karnataka (Kodagu district) | Coffee | Acrocarpus fraxinifolius, Rosewood, Lagerstroemia microcarpa and Jamun | – | Improves agrobiodiversity and overall productivity | Viswanath et al., 2018 |

| Homestead Agroforestry | Kerala | Banana, Black pepper, Tuber crops, Papaya, Fodder grasses, and Ginger | Areca nut, Coconut, Teak, Mahogany, Mango, Jackfruit, and Tamarind | Cows, buffalos, goats, fishery and poultry are common | This systems enhance both ecological and socio economic sustainability | Nair and Sreedharan, 1986 |

| Khejri- based Agroforestry | Rajasthan(Bishnoi community) | Pearl millet, cluster bean, cowpea, and mung bean | Khejri | In the past, goats, and sheep were used. | Enhances farm income, family nutrition, and farm resilience | Kaushik et al., 2020 |

| Large Cardamom-based Agroforestry | Sikkim and West Bengal (Lepchas are the first collectors and users | Large cardamom, Sikkim mandarin, and Ginger | Alnus nepalensis is a main shade tree. Albizia and Melia species are also found | – | Controls insects and pests, and improves farm productivity and resilience | Tamang et al., 2023 |

| Pineapple based Agroforestry | Assam (Hmar community) | Pineapple, cereals, rhizomatous crops, and legumes | Black siris, Artocarpus lakoocha, Aquilaria malaccensis, Rubber, and Parkia | – | Enhances farm income, and conserves soil and water resources | Hazarika et al., 2024 |

| Acacia leucophloea based Agroforestry | Tamil Nadu (Coimbatore and Periyar Districts) | Pearl millet, Horse gram, Cenchrus ciliaris | Acacia leucophloea | The drought-tolerant Kangayam breed of cattle | Nourish the soil by fixing nitrogen and restoring fertility | Viswanath et al., 2018 |

| Toko-based Agroforestry | Arunachal Pradesh (Adi tribes) | Ginger, maize, ragi, tuber crops, and vegetables | Toko palm (Livistona jenkinsiana), tea, and orange | – | Toko is taken as a living fence crop | Deb et al., 2009 |

| Zabo or Dzudu System | Nagaland (Chakhesang tribes in Kikruma village) | Paddy, maize, vegetables, banana, pulses and beans | Mango, guava, and other native trees like siris, alder, and neem | Fish, and Cattle | Soil and water conservation, and improves biodiversity | Bhutia et al., 2025 |

1. Alder-based Agroforestry System (Nagaland)

Indigenous farmers of Nagaland such as Angami, Sumi, Khiamungan, Chakhesang, Chang, Yimchaunger, and Konyak practice alder-based agroforestry (Giri et al., 2024). This is a sustainable ‘Jhum’ practiced by these communities since time immemorial. The alder tree (Alnus Nepalensis D.Don) is a nitrogen-fixing tree that is an indigenous Innovation towards sustainable agriculture and restoration of soil fertility. Nagas specialized and have preferred an excellent cultivation system, in which they incorporated nitrogen-fixing alder trees. In this system, shifting cultivators cut or pollarded the naturally grown alder trees at a height of about one or 2 meters from the ground to obtain coppices. In addition, they plant new saplings and are left to mature during the fallow period. Therefore, this system of shifting cultivation reduces labor input for clearing vegetation. It is believed as one of the most promising bio-physically workable and socially acceptable indigenously innovative adoptions towards soil management. In the Alder-based farming system, most of the seeds are sown in February to April and are harvested from October to December and by this time alder trees produce new shoots. The main intercrops are rice, maize, and Job’s tears; secondary crops are colocasia, potato, soybean, rice beans, and vegetables; tertiary crops are cucurbits, chilies, ginger, onion, tapioca, etc. and other crops are some medicinal, condiments, and ornamental flowers.

2. Bamboo and Pine Homestead Agroforestry (Arunachal Pradesh)

The Apatani community developed this agroforestry system after their longstanding observations and experience. It is believed that the local bamboo (P. bambusoides) and pine (P. wallichiana) are the best combinations as no other shrub or smaller tree could grow and survive under pine and vice versa. This plantation meets various needs of the local community such as timber, planks, poles, fuelwood, medicine, etc. Pine timber is split into sheets called “Santha” and used to roof traditional houses. Locally tapped pine oil or resin are used as mosquito repellents. The resin is also used to cure cracked heels and make varnishes. This system also provides various agroecological services such as nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and production of renewable biomass. In addition to this, these systems are also attracting tourists from various regions.

3. Native Trees-based Coffee Agroforestry (Karnataka)

Coffee Agroforestry in Kodagu, Karnataka, is the practice of growing Coffee plantations under diverse native shade trees to improve biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Kodagu, Coffee is grown under a variety of native shade trees, which is different from other places where coffee is grown as a monoculture or under a single tree species. The high density and diversity of native trees in the coffee plantations of Kodagu have been attributed to the high indigenous diversity of adjacent natural forests. Due to the strict forest protection laws in the district, people have started cultivating exotic trees. The most dominant species in the coffee plantations of Kodagu is an exotic Australian species, Grevillea robusta, which is commonly known as ‘silver oak’. G. robusta in agroforestry plantations is preferred mainly because of its fast growth rate and minimal competition with robusta coffee (Coffea robusta). However, the yield and cupping quality of coffee beans are more under native shade trees.

4. Homestead Agroforestry (Kerala)

The Kerala home garden is a unique indigenous agroforestry system. These home gardens are 3-4 tier structures. The upper layer consists of tree species, usually coconut, areca nut, teak, mahogany, and other short-rotation multipurpose trees. The intermediate layer is occupied by fruit crops and other small trees like bananas, papaya, cinnamon, etc. The first and second layers are dominated by vegetables, medicinal plants, and other food crops. In Kerala home garden, coconut and areca nut are the most prominent, and also Ailanthus triphysa, Mangifera indica, Artocarpus heterophyllus, Tamarindus, Erythrina indica, Macaranga peltata, Thespesia populnea, and Gliricidia sepium are the other preferred tree species. Considering the crop diversity, it varies among home gardens and includes vegetables such as brinjal, ladies finger, cowpea, ash gourd, bitter gourd, snake guard, black pepper, and tuber crops such as colocasia, elephant foot yam. Banana is the common intercrop in home gardens throughout Kerala. Cassava, papaya, fodder grasses, pineapple, Curcuma longa, and Zingiber officinale, are the other common intercrops.

5. Khejri-Based Agroforestry (Rajasthan)

Khejri is the state tree of Rajasthan, and it’s also called the king of the Thar desert. The Bishnoi community of Rajasthan practices agroforestry centered around Khejri (Prosopis cineraria). Integrate the Khejri tree with crops like pearl millet, barley, and other pulse crops (Kaushik et al., 2020). Culturally, the tree has great significance in the lives of people as it is worshiped and conserved by the Bishnoi community due to its enormous benefits. Conservation of this tree is remembered by the bloodshed of Amritha Devi Bishnoi during the Khejarli massacre. Ecologically, it increases soil fertility by adding leaf litter into soil and nitrogen fixation, conserves soil moisture by reducing runoff, and provides fodder for animals and food for people. Therefore, this traditional agroforestry system played a significant role in the lives of desert people.

Moreover, the Khejri tree supports the growth of other fruit trees and holds cultural significance, being worshiped during Janmashtami ( the birthday of Lord Krishna as per Hindu traditions) and honored and worshiped by communities like the Bishnoi. The tree is also resilient to climate extremes as it can withstand and adapt to frost and drought and survives under both high and low temperatures.

6. Large Cardamom-based Agroforestry (Sikkim and West Bengal)

Large Cardamom-based agroforestry is a purely traditional land use system practiced by indigenous communities of Sikkim and Darjeeling region of West Bengal (Tamang et al., 2023). This traditional adaptive management provides environmental services, ecological health, biodiversity conservation, and socio-economic well-being of traditional communities. Large Cardamom (Amomum subulatum) is commonly known as Alaichi in Nepali and Badi Ailachi in Hindi; and popular as black cardamom, and black gold. It is a shade-loving, perennial herbaceous plant, native to Sikkim. It is believed that the original community Lepchas are the first collectors of Cardamom capsules from natural forests and users.

Large Cardamom grows well under the shade of trees, requires high moisture, mean annual rainfall of 1500- 3500 mm with soil pH of 4.5-7, and is usually grown at a high altitude of 600-2000m. As it is a shade-loving plant it grows under various trees like Alnus nepalensis, Albizia sp., Ficus nemoralis, Ficus hookeri, Nyasa sessiliflora,Osbeckia paniculata, Viburnum cordifolium, Litsaea polyantha, Macaranga pustulata, Saurauvia nepalensis, Machilus edulis, Melia composite, Engelhardtia acerifolia, Eurya acuminata, Leucosceptrum canum, Maesa chisia and Symplocos theifolia . Among these trees, Alnus nepalensis is found to be ecologically and economically viable as shade trees. This traditional agroforestry system is a closed system that does not need any external inputs.

7. Pineapple-based Agroforestry (Assam)

This Agroforestry system is practiced by an indigenous Hmar community in southern Assam (Hazarika et al., 2024). They have moved towards high-valued settled cultivation from the unsustainable shifting cultivation land to a pineapple agroforestry system. The export of these organic pineapples is fetching a higher price in the global market through international expansion efforts. In addition, multipurpose trees such as Albizia lebbeck, Artocarpus lakoocha, Aquilaria malaccensis, Hevea brasiliensis, Parkia timoriana, etc. are also grown as shade trees, which provide diverse benefits such as food, fuelwood, timber, and cash crops.

In this Agroforestry system, communities follow slash-and-burn of secondary forest in January-April. Intentionally retain matured native trees to provide shade for understory crops and reduce soil erosion. Burnt plant residue is left on the surface of the land to enhance soil fertility. Short-term annual crops (cereals, rhizomatous crops, legumes, and spices) are planted along with retained trees. In September-November, pineapples are grown with a spacing of 0.7 – 0.8 m (4 pineapple plants/m2). They practice sustainable agronomic management practices such as zero tillage, manual weeding, and no synthetic fertilizers. In addition to pineapple, fruit trees like bananas and areca are also planted as border trees, serving as living fences, windbreaks, and shelterbelts. After 8–10 years, pineapple yield starts to decline. In such cases, Albizia procera trees are being replaced by economically valued species. Additionally, fruit trees, including litchi and mango are also planted. Apart from this, commercial trees like rubber are planted in the pineapple agroforestry system in some selected sites, specifically those older than 15 years and with limited economic gain. The addition of fruit trees, leguminous trees, or rubber in agroforestry systems results in significant economic benefits.

8. Acacia leucophloea-based Agroforestry (Tamil Nadu)

This system is prevalent in dry tracts of Coimbatore and Periyar Districts where annual rainfall is very scarce around 600 mm (Viswanath et al., 2018). Acacia leucophloea is resistant to drought, improves soil fertility through nitrogen fixation, and has quick regeneration ability after the first rains. Generally, intercropping of pearl millet and horse gram is taken. The 15-20-year-old trees develop high biomass and yield up to 100 kg pods annually. Farmers thin them out to between 25 and 60 per ha. The pods are excellent high-protein fodder supplements in the dry season. Nowadays, farmers shift towards planting Cenchrus ciliaris (a hardy fodder grass that regenerates naturally soon after the first rains) instead of cereals and pulses because of uncertain rainfall and drought. In addition, most of the farmers are now shifting from an agrosilvopastoral to a silvopastoral system. The drought-tolerant “Kangayam” breed of cattle developed in this area is a much-coveted bull in an annual bullfighting festival or ’Jallikattu’ in Tamil Nadu.

9. Toko-based Agroforestry (Arunachal Pradesh)

Toko-based traditional Agroforestry is commonly practiced by Adi tribes (Minyong, Padam, Pasi, and Pangi) of Arunachal Pradesh. The Toko tree (Livistona jenkinsiana Griff) palm belongs to the Aracace family and is multipurpose (Deb et al., 2009). The tribal people (Adi, Galo, Nyshi, Mishig, etc.) of Arunachal Pradesh have been using this tree since time immemorial. Toko trees are planted in either plantation or agroforestry. In traditional agroforestry, during Jhum cultivation trees are planted around the boundary of the field and in the field. In between the trees, intercrops are grown during the first 6 years of the new Jhum land establishment. The growth habit and architecture make tokopalm compatible with developing agroforestry systems. It does not produce much shade, hence many seasonal crops and vegetables can be grown under this tree. They practice various combinations with the Toko tree: toko + ginger, toko + tea, toko+orange (toko is taken as living fence crop), toko + tuber crops (sweet potato and tapioca), and toko + maize (for initial 4-5 years).

10. Zabo system (Nagaland)

The term “Zabo” refers to the impoundment of water. The Zabo or Dzudu or Ruza system is an indigenous sustainable farming system comprising forestry, horticulture, agriculture, fishery, and animal husbandry with a well-suited soil and water conservation base on one hill (Bhutia et al., 2025). The Zabo system of farming is practiced by the Chakhesang tribes in Kikruma village in Nagaland. It has 3 major strata, the protected forest on the hilltop, intermediate strata consisting of a water harvesting pond, cattle shed, and a paddy field at the lower strata. In this system, the water from hill slopes is collected in the ponds with seepage control, which is also connected with various silt retention tanks before the runoff water enters the pond. The water from the ponds enters the orchard plantations and then to livestock; it carries all the urine and cow dung of the animals to the paddy field. These paddy fields are used to rear fish, which gives an additional income to the farmers. The main crop is paddy; fruits and vegetables are grown along the terraces near the ponds, cattle sheds, and water channels. Vegetations include mango, guava, banana, papaya, pomegranate, maize, potato, squash, colocasia, cucumber, cabbage, garlic, tree tomato, and king chili, to name a few. In addition, pulses such as rajma (Phaseolus vulgaris) and beans (Vigna sp.) are also cultivated. Some of the native trees like siris (Albizia lebbeck), alder (Alnus nepalensis), and neem (Azadirachta indica) are also planted near the bunds, which are the main source of organic fertilizer, add leaf litter into the soil.

Further Reading: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32463-6_5

Conclusion

Indigenous agroforestry systems have developed over centuries through cultural and biological adaptations, embodying accumulated wisdom and innovations derived from experiential learning and careful environmental observation. This accumulated knowledge and experience were transferred from one generation to another orally by the elders of the ethnic communities. Farming practices are not only livelihood activities for ethnic communities but also interlinked with economic, social, cultural, and religious beliefs. Many cultural ceremonies are directly linked to agricultural operations like sowing and harvesting, which are forms of gatherings and sharing innovations. The slash-and-burn cultivation is a primitive farming system that has its own merits and demerits. The defect of shifting cultivation lies with deforestation, soil fertility loss, low income, and land rotation with lower inputs. However, some traditional knowledge, like agrobiodiversity, selection of crops, and use of local varieties that are resistant to pests and diseases, are some of the advantages of shifting cultivation.

In the era of shifting cultivation, some prominent indigenous agroforestry practices were developed by various indigenous groups in many parts of the country, which are sustainable land use management practices. Alder-based agroforestry system in Nagaland is the sustainable practice for the restoration of soil fertility in Jhum land, where nitrogen fixing and multipurpose alder trees were incorporated. Another example is Bishnoi Khejri-based Agroforestry centered around the Khejri tree, which has economic, ecological, and cultural significance in the Thar desert due to its ability to grow and withstand harsh climatic conditions. Some of the other examples are traditional home gardens, large cardamom-based Agroforestry, Toko-based agroforestry, bamboo and pine-based, and Zabo practices. These sustainable traditional practices, relying on low-input methods, manage to produce multiple outputs and are crucial for the livelihood needs of millions of indigenous people. Therefore, Indigenous Agroforestry practices not only sustain biodiversity but also safeguard traditional knowledge, cultural identity, and community resilience. By recognizing and supporting these systems, we can promote sustainable development, enhance food and nutritional security, and conserve precious ecosystems for future generations.

Visit our recent blogs:https://whereagroforestrymeetsagriculture.com/top-10-profitable-agribusiness-ideas-in-india/

References

Akter, R., Hasan, M.K., Kabir, K.H., Darr, D. and Roshni, N.A., 2022. Agroforestry systems and their impact on livelihood improvement of tribal farmers in a tropical moist deciduous forest in Bangladesh. Trees, Forests and People, 9, p.100315.

Bhutia, P. L., Bhutia, K. G., Panwar, P., Singh, N. R., Pal, S., & Khola, O. P. S. (2025). Traditional Agroforestry Systems of North-Eastern India: An Overview. Sustainable Management and Conservation of Environmental Resources in India, 207-234.

Bundela, D. S. 2007. Water Management in Northeast India – Some Case Studies. Edited by Kaledhonkar et al. CSSRI, Karnal. p. 40-46.

Deb, S., Arunachalam, A. and Das, A.K., 2009. Indigenous knowledge of Nyishi tribes on traditional agroforestry systems.

Dinesha, S., Raj, A., Bhanusree, M. R., Balraju, W., Rakesh, S., Raj, W. G., Jha, R. K., Neeraj, ., & Kumar, K. (2022). Agroforestry Assisted Natural Farming in India: Challenges and Implications for Diversification and Restoration of Agroecosystem. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change, 12(12), 1053–1069.

Giri, K., Mishra, G., Jayaraj, R. S. C., & Tsopoe, M. (2024). Agrobiodiversity and Crop Productivity of the Alder-Based Jhum Farming System in Khonoma Village, Nagaland, India. In Shifting Cultivation Systems (pp. 65-71). Springer, Cham.

Hazarika, A., Kurmi, B., Francaviglia, R., Sileshi, G. W., Paramesh, V., Das, A. K., & Nath, A. J. (2024). The transition from shifting cultivation to indigenous agroforestry as a nature-based solution for land restoration in the Indian Eastern Himalayas. Ecological Indicators, 162, 112031.

Kaushik, N., Arya, S., Yadav, P. K., Bhrdwaj, K. K., & Gaur, R. K. (2020). Khejri (Prosopis cineraria L. Druce) based agroforestry systems in the arid and semi-arid region: supporting ecosystem services. Indian Journal of Agroforestry, 23(2), 01-09.

Nair, M. A., & Sreedharan, C. (1986). Agroforestry farming systems in the homesteads of Kerala, Southern India. Agroforestry systems, 4, 339-363.

Tamang, B., Shukla, G., & Chakravarty, S. (2023). The urge of conserving tradition from climate change: A case study of Darjeeling Himalayan large cardamom-based traditional agroforestry farming system. Nature-Based Solutions, 3, 100064.

Taka, T., & Tangjang, S. (2015). Original research article sustainable approach: paddy-cum-fish and bamboo-cum-pine agroforestry in Ziro valley, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Journal of Bioresource, 2(1), 50-57.

Viswanath, S., Lubina, P. A., Subbanna, S., & Sandhya, M. C. (2018). Traditional Agroforestry Systems and Practices: A Review. Advanced Agricultural Research & Technology Journal, 2(1), 18-29.