Background

We recently visited Warichora, a tourist spot in the Garo Hills of Meghalaya. There, we observed black pepper (Piper nigrum) being cultivated on native host trees. Those were chaplasha (Artocarpus chaplasha), Indian coral tree (Erythrina indica), Schima wallichi, sal (Shorea robusta), and Indian mahogany (Toona ciliata). This reminded me of my parents’ traditional practice of cultivating betel vine on drumstick (Moringa oleifera) and Indian coral tree (Erythrina variegata) along with boundary planting of Agati (Sesbania grandiflora) and Gliricidia sepium.

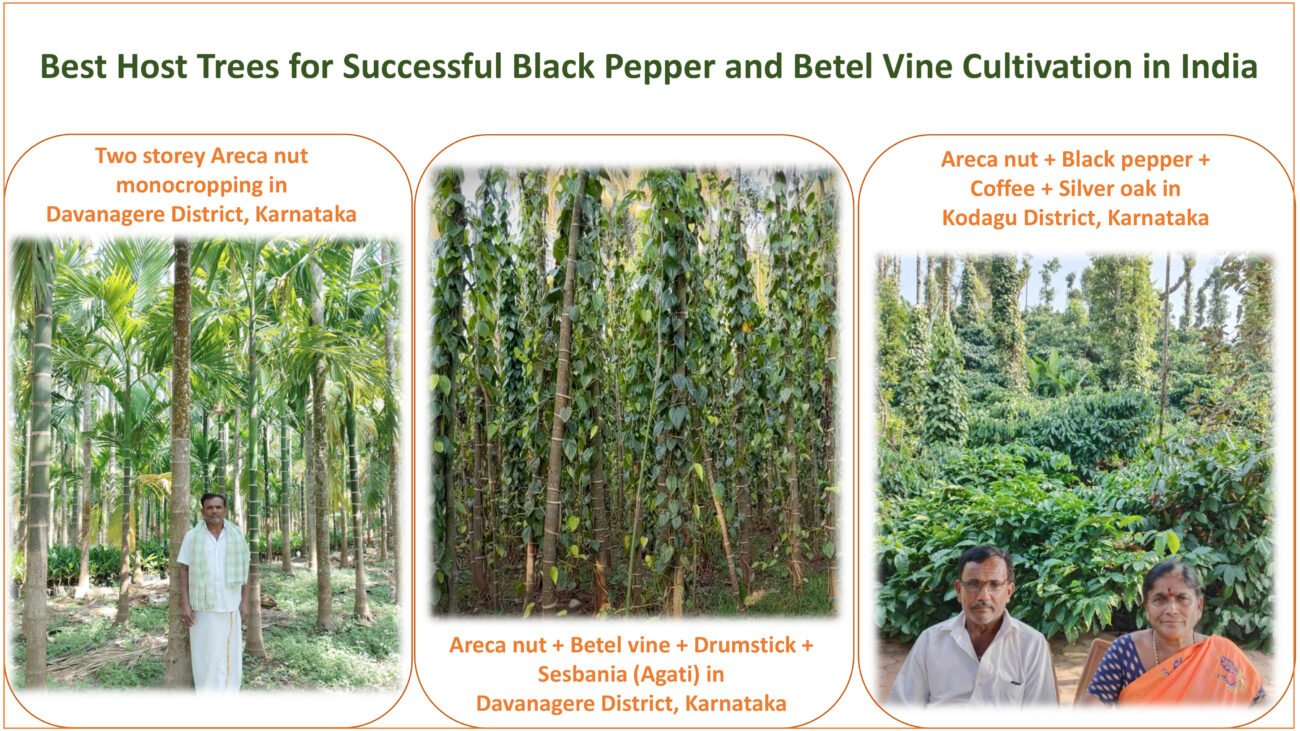

Betel vine with areca nut, drumstick, and sesbania (agati) in Davanagere District, Karnataka

My father often recalled how his great-grandfather (Kallappa) once worked in the betel leaf plantations. This thrived along the far bank of the Tungabhadra River, somewhere near present-day Shivamogga. Subsequently, the family moved across to the central part of Karnataka and eventually settled down in Siddanuru village of Davanagere. There, they began cultivating betel vine and millets in the dry central zone, carefully protecting their fields with strong shelters and windbreaks. Unfortunately, over the years, most farmers in that region have shifted to high-density areca nut monocropping, driven by market demand, labour issues, and ease of management.

Two-storey areca nut monocropping in Davanagere, Karnataka

A similar trend is emerging in the Garo Hills, where farmers closer to urban centers, better income, ease of management, lack of awareness about the importance of native trees, and marketability are clearing native trees to establish high-density areca nut monocropping systems. This ongoing transition raises some important questions in our minds:

1. How did areca nut come to India?

Historical records suggest that areca nut reached India centuries ago through trade and cultural exchange. Now it has become deeply embedded in rituals, traditions, and livelihoods across the country.

2. Why is areca nut everyone’s favorite commercial crop?

Due to its steady market demand, quick returns compared to other tree crops, and the relative ease of management under monocropping systems, areca nut is highly attractive to farmers seeking a stable and high income.

3. Why are host trees being replaced with areca nut in the cultivation of black pepper and betel vine?

Nowadays, the areca monocropping has replaced the native host trees because farmers perceive areca nut plantations as more profitable and less labor-intensive. However, this shift often comes at the cost of ecological balance and long-term sustainability.

4. How can we tackle this dominance of areca nut?

To tackle this, we must identify and promote commercial host trees best suited for black pepper and betel vine cultivation. At the same time, these trees should support farming systems that are acceptable and profitable for farmers and ecologically sustainable.

Blending traditional knowledge with scientific studies can help us to find the best solutions that honor both people and nature. If we identify host trees that support crop productivity while conserving biodiversity, India can continue to thrive as a landscape where livelihoods, culture, and ecology interweave, just as they once did in rural villages

Motivated by this concern, we have initiated a research study to identify and evaluate commercially suitable native host trees for the cultivation of high-value spice and leaf climbers in the Garo Hills of Meghalaya.

5. Why are black pepper and betel vine hold significant importance in India?

Black pepper holds significant cultural, economic, and ecological importance in tropical and subtropical regions of India, especially in states like Kerala, Karnataka, Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura. People value it as a high-value spice crop, and demand for it remains strong both domestically and in export markets. They enhance farmers’ income and reduce crop failure when cultivated in mixed cropping systems. Black pepper is also known as black gold; it was exchanged for or used like gold in ancient times due to its high value and rarity. It was traded for gold and silver by the Romans and was sometimes even used as legal tender in the Sixteenth century.

The betel leaf is intertwined in the spiritual and social lives of people in India. In South India, people offer it to Lord Anjaneya, and it also holds a significant place in every Shubha karya (auspicious ceremony). In North India, too, it carries the same reverence, marking sacred and festive occasions. This tradition extends to the North East as well, where the betel leaf continues to be a cherished part of social gatherings, symbolizing friendship, togetherness, and community bonds. In the Khasis of Meghalaya, kwai (betel quid) is an integral part of their lives. In fact, when anyone dies in the Khasi Hills, it is said that the person has gone to heaven to have kwai with God. Beyond rituals, people have long regarded the betel leaf as a symbol of respect and hospitality, offering it to guests as a warm gesture.

Farmers often train these climbers on native trees, avoiding the need for artificial supports and helping conserve biodiversity in many areas. By integrating with existing plantations such as arecanut and coconut, they diversify farm outputs, stabilize yields, and reduce economic risks. Selecting the right host tree is crucial for their growth, productivity, and longevity. Ecologically, they improve resource use efficiency, maintain soil cover, and support sustainable farming. Overall, they play a key role in agroecology, climate resilience, and rural livelihoods.

Black Pepper

A perennial climbing vine that uses adventitious roots to anchor on the host trees for support. It grows well in warm, humid climates with well-drained, organic-rich, fertile soils.

An ideal host tree for pepper should have a tall and clear bole and tap root system that does not compete with black pepper for water, nutrients, and solar radiation; a slender, but strong trunk with a rough surface. The host tree should also possess the ability to withstand regular pruning and pollarding, and have economic value after the life span of the crop. Further reading: https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2020.912.261

The Growth Under Native Host Trees

Selection: The trees with tall and clear boles, long-lived, self-pruning, rough bark for easy anchorage, and sparse canopy, like Silver oak (Grevillea robusta), Agar wood (Aquilaria malaccensis), Pajanelia or Payyani (Pajanelia longifolia).

The Best Host Trees for Black Pepper

- Silver Oak: It is a fast-growing, tall tree with a straight trunk that provides partial shade. It also has rough bark, which helps to ensure easy anchorage. One of the globally recognized indigenous coffee-based agroforestry systems in the Kodagu region of Karnataka grows black pepper and coffee under commercially important Silver oak trees.

Coffee with areca nut, black pepper, and silver oak in Kodagu District, Karnataka

- Agar wood: A medium to tall evergreen tree (15–20 m) with a straight bole and moderately rough bark, ideal for black pepper vines. Its moderately open canopy provides filtered sunlight. Intercropping with pepper ensures dual income from berries and high-value agarwood resin. Regular branch pruning to regulate shade; deep-rooted habit reduces competition with pepper roots.

- Pajanelia or Payyani: A fast-growing deciduous tree (20–25 m) with a straight trunk and fissured bark, offering strong support for pepper vines. Its light canopy allows good light penetration, while its hardy, long-lived nature ensures sustainability. Also valued for timber and shade. Periodic lopping to maintain filtered light; well-suited for intercropping and mixed plantations.

Planting: Pepper cuttings (2-3 node rooted cuttings) are planted at the base of host trees during the monsoon. The spacing between the vines depends on tree distribution; usually 2–3 m from the tree base.

Management: Regular pruning of the host tree canopy is important to balance light and shade. Mulching with leaf litter from native trees will improve soil fertility and moisture conservation. Organic manures such as Form Yard Manure (FYM) and compost should be applied annually.

Advantages: Pepper benefits from natural shade and organic matter. System conserves biodiversity and reduces monoculture risks.

Growth Under Arecanut and Coconut Plantations

Arecanut: A tall, slender palm commonly grown in homesteads and widely used as a traditional host in South India. It provides vertical support and partial shade for pepper vines. However, in some cases, the thin trunk often requires additional support for better anchorage.

Coconut: A tall palm with a straight trunk that offers shade and support to pepper vines. While effective as a host, its great height makes vine management and harvesting more difficult.

Planting: Pepper cuttings planted at the southern or western side of the palm base to avoid direct sunlight. One to two pepper vines per arecanut palm.

Management: Arecanut canopy naturally regulates shade; occasional thinning may be required. Organic manure, compost, and neem cake are added at the base of vines. Regular irrigation during summer ensures berry development.

Advantages: Efficient land use, a dual cropping system enhances income. Pepper vines climb smoothly on straight arecanut and coconut trunks.

Betel Vine

It is a shade-loving perennial climber that requires moist, fertile soil. Sensitive to direct sunlight and wind; prefers cool, humid microclimates with proper shade.

The Growth Under Native Host Trees

Selection: Shade-providing species like Indian coral tree (Erythrina variegata), drumstick (Moringa oleifera), and chram or chaplasha (Aurtocarpus chaplasha). Trees with spreading branches and fissured bark are suitable for better anchorage.

The Best Host Trees for Betel Vine

- Indian Coral Tree: A medium to tall deciduous tree with a straight trunk and rough bark, making it an excellent support for climbers. Its light, spreading canopy provides filtered shade, ideal for betel vine and black pepper cultivation. The tree grows quickly, establishes easily, and is hardy under diverse soil conditions. In addition to serving as a host, it improves soil fertility through nitrogen fixation and leaf litter, contributing to sustainable agroforestry systems. Requires periodic lopping to regulate shade and encourage straight growth. As it is deciduous, complementary shade plants or structures may be needed to maintain a stable microclimate during leaf fall.

- Drumstick: A fast-growing, medium-sized deciduous tree commonly used as a support for betel vine. Its straight trunk and rough bark provide good anchorage, while the light canopy ensures filtered shade—ideal for the delicate betel leaves. Being deep-rooted, it minimizes competition for nutrients and moisture. Additionally, drumstick enriches the soil through leaf fall and serves as a multipurpose tree valued for its pods, leaves, and medicinal uses, thereby enhancing the overall sustainability of the betel-based agroforestry system. Regular lopping of branches is needed to maintain optimum shade. Interplanting with other shade-regulating species further improves microclimate for betel cultivation.

- Chaplasha: A large, evergreen to semi-evergreen forest tree native to Northeast India and adjoining regions. It grows tall (20–30 m) with a straight bole and moderately rough bark, making it suitable as a support tree for black pepper. The canopy is fairly dense but can be managed through pruning to provide filtered shade, which benefits pepper vines. Being a deep-rooted, long-lived species, it competes less with shallow-rooted vines and ensures sustainable support. Its timber is valuable, adding economic returns in a pepper-based agroforestry system. Regular pruning of branches is essential to regulate light penetration. Due to its large size and dense canopy, planting should be well-spaced to avoid excessive shading.

Planting: Cuttings planted near tree base with a shade net or thatch covering during initial establishment. Requires cool, humid microclimate; hence intercrops like banana can be used for additional shade.

Management: Prune trees to maintain filtered shade (50–60% shade ideal). Organic mulching, farmyard manure, and compost are regularly added. Sprinkler or drip irrigation during the dry season. Windbreaks are essential to prevent leaf tearing.

Advantages: Reduced input costs due to natural shade and microclimate regulation. Enhances traditional agroforestry biodiversity.

Growth Under Arecanut Plantations

Areca is commonly used in betel vine gardens, but betel vine cultivation performs best under trees and other artificial shading structures.

Host Arrangement: Betel vine is grown on arecanut palms with support sticks, coir ropes, or bamboo frames. Arecanut provides natural shade and vertical support, but extra shade (banana or shade net) is often required.

Planting: Vine cuttings are planted at the palm base, generally 2 cuttings per palm. Support is given initially until vines climb.

Management: Frequent irrigation (light and regular). Organic manures at regular intervals. Preventive measures for leaf rot and wilt diseases (common under humid arecanut shade). Wind protection is essential.

Advantages: The areca nut–betel vine system is traditional in many parts of India. Provides dual income with high-value betel leaves, along with arecanut yield.

Both systems integrate well into sustainable agroforestry, improving land productivity, farmer income, and ecosystem services.

Inspiring Success Stories

Some stories highlight the resilience and innovation of farmers across India in cultivating black pepper and betel vine.

Black pepper

Karnataka

High-Value Black Pepper Farming in Kodagu District

In Kodagu, Karnataka, farmers have adopted high-density planting and organic farming techniques to boost black pepper yields. By integrating silver oak trees as support structures, they have enhanced productivity and profitability. This approach has transformed traditional farming practices, leading to increased incomes and sustainable agriculture. Further reading: https://doi.org/10.1080/02759527.2025.2504241

Assam

Black Pepper Farming for Elephant Conflict Resolution

The Diya Foundation introduced black pepper cultivation as a solution for farmers in Assam affected by elephant raids. This initiative not only provided additional income but also helped in mitigating human-elephant conflicts, leading to a 30-40% increase in farmers’ income.

Meghalaya

Organic Black Pepper Farming in West Garo Hills

Padma Shri awarded Nanadro B Marak from Meghalaya’s West Garo Hills began organic black pepper farming in 1986. His commitment to chemical-free practices has earned him the recognition of Padma Shri, and he is now getting a steady income from his organic pepper plantation.

Black pepper cultivation using decomposed and decaying tree logs in West Garo Hills

The Garo farmers of West Garo Hills adopt an indigenous technology to increase the yield of black pepper by using decomposed and decaying tree logs. Keeping these logs in the root zone area of the plant is reported to increase the fertility status and moisture retention capacity of the soil. It also improved the plant growth, increased the size of berries and length of the fruit-bearing vine, and minimized the mortality rate of the plant under water stress. For further reading: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349428115

Community-Based Black Pepper Farming in North Garo Hills

In North Garo Hills, farmers cultivate black pepper under the canopy of areca nut trees, yielding a unique and aromatic pepper variety. This community-based approach has preserved traditional farming methods and supported local livelihoods. These farming methods encouraged fringe farmers to adopt them in their arecanut monocropping systems.

Betel Vine

Meghalaya

Betel leaf is mainly cultivated in the Amlarem Block of West Jaintia Hills District; Kharkutta, Samanda, and Songsak Blocks of East Garo Hills District; Chokpot Block of South Garo Hills District; Dalu and Dadenggre Blocks of West Garo Hills; and Pynursla Block of East Khasi Hills. Cultivation is practiced through an innovative agroforestry system, where vines are grown in association with various naturally occurring trees and shrubs, as well as over areca nut palms.

An indigenous War Khasi betel leaf agroforestry system in the Pynursla block of East Khasi Hills

A betel leaf agroforestry system was developed through generations of experiential learning and traditional Khasi knowledge. This system is highly sustainable, promotes native plant diversity, and exerts minimal impact on plant diversity. In Nongkwai village, the War Khasi people have transformed lowland tropical forests into betel leaf agroforestry systems, where vines are intercropped with a variety of native trees and shrubs, resulting in structurally complex systems that mimic the original forest. In natural forests, 160 plant species were recorded, while in betel leaf agroforestry, 159 species were documented. Among these, 34 tree species, 13 shrubs, and 14 herbs were common to both systems. Key cultivation practices include tree lopping to regulate sunlight and recycle nutrients, propagating vines through stem cuttings, and planting during the June to August (monsoon season). The study concluded that conversion of natural forest to betel leaf agroforestry in South Meghalaya does not significantly affect tree and herb diversity. Further reading: https://doi.org/10.13057/asianjfor/r020101

Maharashtra

Traditional Betel Vine-based agroforestry practice

A recent (August 2025) study documented the role of traditional betel vine agroforestry in sustaining rural livelihoods, particularly in Maharashtra. This system is also practiced in parts of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu, making the findings relevant to these places, only to those that share similar agroclimatic and ecological zones. The study reported average practice areas of 0.11–0.23 ha, featuring 12 plant species, mainly supported by native tree species of Erythrina, Sesbania, and Moringa. Farmers adopted zigzag, strip, and square planting patterns. Additionally, to address the dominance of areca nut, integrating alternative commercial tree species alongside native trees is vital. Studies further suggested that stronger market linkages and a price support system are needed to sustain this indigenous system. Further reading: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-025-01289-3

Bangladesh

Betel leaf farming with native trees by Khasia indigenous communities in Moulvibazar District

A long‐standing forest‐based betel farming” or “Bri / paan jhum practice (growing betel vine on naturally‐growing native supporting trees)practiced rather than clearing forests. This system uses tree species like Artocarpus chaplasha, Anthocephalus chinensis, Vitex spp., Toona spp., etc. as hosts. This practice financially profitable (a study in Sylhet reported 4.47 benefit‐cost ratio, indicating strong returns), conserves biodiversity, and the farms serve as refuges for many tree and plant species, wildlife, etc. Further reading: 10.1080/14728028.2005.9752528

Conclusion

Selecting the right host tree is pivotal for the successful cultivation of black pepper and betel vine. Trees like Silver Oak, Indian Coral, and Drumstick provide the necessary support and environmental conditions essential for these crops to thrive. Understanding the growth habits of the vines and the characteristics of potential host trees, farmers can ensure a productive and sustainable cultivation process. Our observations suggest that non-native tree species, when integrated thoughtfully with local knowledge systems, can also become part of bioregional lifeways. For instance, silver oak, originally introduced for timber and shade, has been woven into the fabric of coffee agroforestry landscapes in Kodagu, Karnataka. Farmers adapted their management through pruning, intercropping, and careful water use, thereby aligning these trees with local needs while minimizing ecological stress. Similarly, we can observe that some non-native trees, once brought from beyond their native range, have become an important component of agroforestry and home gardens, providing durable wood, shade, income, and much more. These case studies show that non-native trees are not always ecological intruders but can become resources that support place-based living, sustain livelihoods, and ensure long-term ecological harmony.

FAQs

- Can black pepper and betel vine be grown on the same host tree?

Yes, both can be cultivated on the same tree, provided the tree offers sufficient support and the vines receive adequate care.

- How often should I prune the host tree?

Pruning should be done annually to maintain the tree’s health and ensure it provides optimal support for the vines.

- Are there any trees to avoid as host plants?

Trees with smooth bark, shallow root systems, or those that are short-lived should be avoided as they may not provide adequate support or may compete with the vines for nutrients.

- How can I improve soil fertility for these crops?

Incorporate organic matter like compost or well-decomposed manure into the soil to enhance fertility and support healthy vine growth.

- What pests should I be aware of?

Monitor for pests like aphids, mealybugs, and root-knot nematodes, which can affect both the host tree and the vines. Regular inspection and organic treatments can help manage these pests.

I enjoyed reading this article. Thanks for sharing your insights.