Defender of Land, Legacy of Indigenous Agroecological Sovereignty

Background

When revisiting India’s colonial resistance and partition horror, many stories focus on Bengal and Punjab, but the Northeast also has silent and hidden stories of colonial resistance. This resistance, rooted not only in politics but in deep ecological guardianship. One such story is the brave defenders, U Tirot Sing Syiem (Chief) of Nongkhlaw, Khasi Hills of Meghalaya. The first hero fought against British rule in the 1830s, interestingly, before the Sepoy Mutiny (the first Indian Independence Struggle, 1857). He is also often remembered for his military resistance to British rule; his struggle is intrinsically connected with land rights, indigenous agriculture, and traditional knowledge. His legacy offers a vital lens through which to examine the indigenous relationship with land, the threats of colonial land policies, and the importance of community guardianship over natural resources.

Agriculture and Trade in the Khasi Hills Before the British Invasions

It is important to understand the socio-economic landscape of the Khasi Hills in the 1830s before looking into the U Tirot Sings’ resistance to colonial rule. The Khasi way of life was mainly built on shifting/ jhum agriculture, agro-ecological balance, and local governance, all interconnected through centuries of tradition and indigenous wisdom. For Khasis, agriculture wasn’t just an economic activity; it was a cultural expression of guardianship and identity. Shifting cultivation was followed in community-based land tenure systems, which means land was not privately owned but held collectively under the authority of the Syiem (chief) and administered through the Dorbar (village council). It had also reflected a deep ecological connection where cultivation co-existed with bamboo thickets, forest patches, sacred groves, and water systems.

These community-led agriculture-forest systems fostered both biodiversity and food security. Chiefs were the guardians of trade routes and managed resources based on community ownership and customary law. These sustainable and harmonious arrangements were disturbed by the intrusion of the British East India Company.

Before the British intrusion, the Khasi Syiems governed the southern foothills with deep cultural identity and ecological responsibility. The region was prosperous with bountiful harvests, and trade from agriculture, horticulture, and forest products. Khasis were well-versed in terrace farming and also acted as guardians of forest resources, traded limestone, iron, oranges, spices, and timber in the markets (haats) of Sylhet plains in exchange for salt, tobacco, fish, oil, utensils, and livestock.

British Expansion and the Threat to Agroecology, Land-Based Livelihoods, and Market Systems

After the Anglo-Burmese War and the Treaty of Yandaboo in 1826, the British sought a military and trade route through the Khasi Hills to connect the Brahmaputra Valley in Assam with the Surma Valley in Sylhet of Bangladesh. This proposed road was meant to pass through the Nongkhlaw area, ruled by U Tirot Sing, who allowed the British survey mission, hoping for mutual benefit. Later, he realized the British expansionist tactics and encouragement of fertile foothills, the disruption of traditional land management and market systems, and the harassment of Khasi women during road construction.

Realizing the threat to Khasi self-rule, agroecology, and livelihoods, he led a rebellion against the British in 1829, sparking the Anglo-Khasi War (1829-1833). Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, his guerrilla campaign lasted for four years across harsh hilly terrain. resistance across difficult terrains. U Tirot Sing was captured and later died in British custody in Dhaka on July 17, 1835.

“It is better to die an independent king than to reign as a vassal.”

U Tirot Sing

Divide and Rule: Administrative Fragmentation and Its Aftermath

Post-war, the British took indirect control through the Khasi Hills Political Agency (1835), fragmenting cohesive polities like the Khasi-Jaintia communities. While some chiefs also supported cooperating with the British for land exchanges. The foothill markets (Haats), once centres of agriculture-linked trade, came under Company surveillance, which disturbed and redirected indigenous wealth through colonial roads and markets. This severely disturbed the Khasi communities’ livelihood, dependent on shifting cultivation and natural resources like forest products and limestone etc.

Later, during partition, the Radcliffe Line separated trade routes and kinship links, embedding displacement, illegal trade, and land insecurity into the region’s modern history.

Lessons for Agroforestry and Sustainable Agriculture

Climate change, land degradation, and commercialization of agriculture pose a challenge, to food systems, traditional ecological knowledge is being revalued for its resilience, sustainability, and community embeddedness. U Tirot Sings resistance offers following three key insights.

1. Land as Common Property, Not Commodity: The Khasi system treats land as a shared resource, much like many traditional agricultural models that rely on community management of landscapes. The current push for land privatization unscientific anthropogenic activities, and monocultures is worrisome.

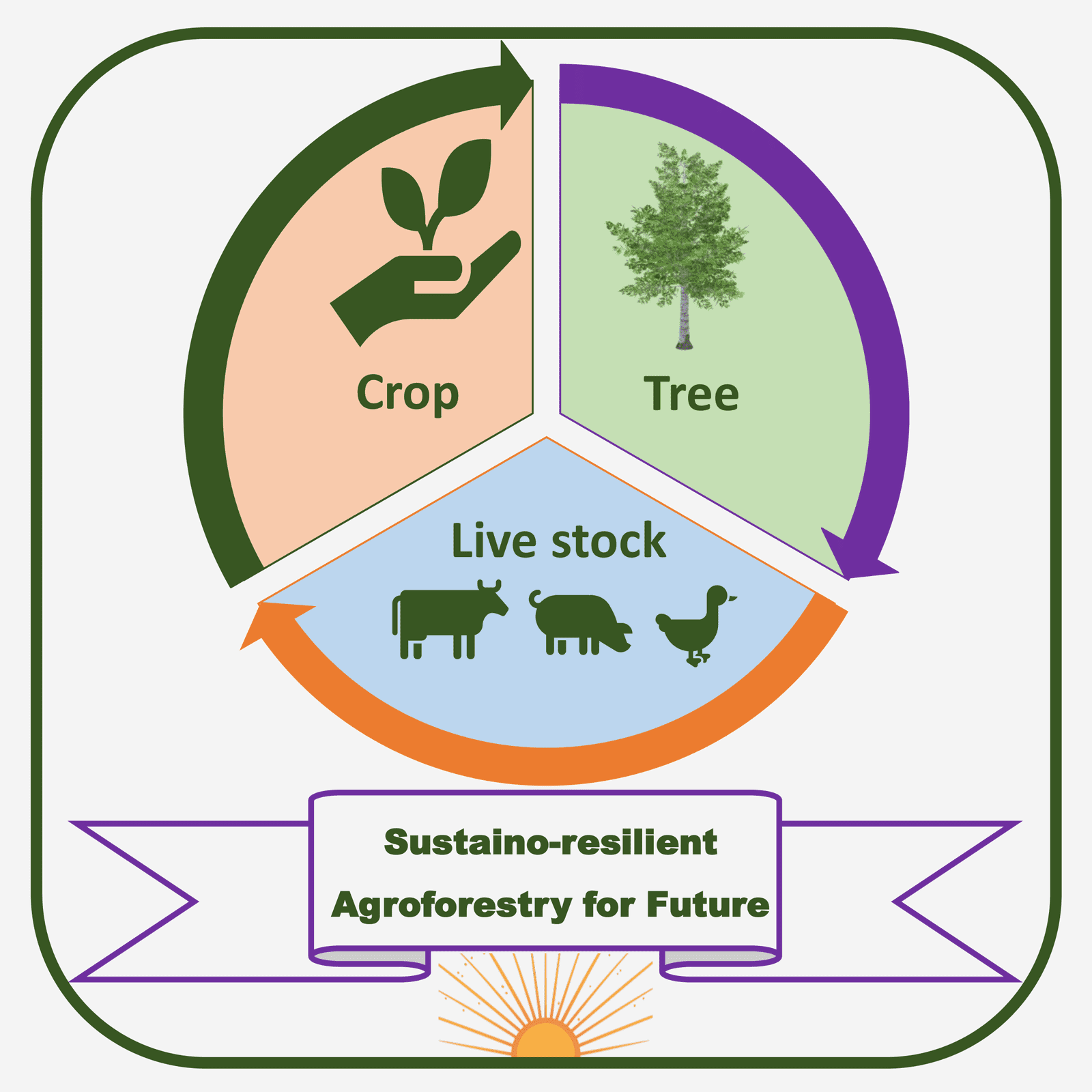

2. Agroforestry Is Not New to Northeast India: The Khasi people have cultivated agriculture and horticulture crops in different forests and bamboo patches on slopes. These traditional agriculture-forestry models are inherently biodiverse, climate-resilient, and culturally embedded. U Tirot Sing’s defense of these landscapes preserved what we seek to promote through agroecology.

3. Decolonizing Agriculture, Food Sovereignty, Cultural Identity: The British rule imposed extractive and hierarchical land systems. U Tirot Sing’s resistance reminds us to question these legacies. Indigenous agriculture is not just about growing food; it’s about preserving agro-ecological intuition, seed traditions, and safeguarding community rituals.

Conclusion

As we focus on agriculture and forestry, his story reminds us that land-based struggles are more than political; they are agroecological, cultural, and socioeconomical. In remembering U Tirot Sing, we honour not just a freedom fighter, but a guardian of indigenous agricultural landscapes, whose legacy continues to inspire sustainable futures in the hills he once defended.

As India looks east with its Act East Policy, it is crucial to understand and acknowledge the unresolved issues of land, identity, and ecology in the Northeast. It must align with indigenous knowledge, customary land rights, and traditional agricultural wisdom that once made these hills prosperous and self-reliant.

Further Reading

Mills, A. J. M. (1901). Report on the Khasi Jaintia Hills: 1853. Shillong: Assam Secretariat Printing Office.

Syiemlieh, D. R. (2008). Trade and markets in the Khasi Jaintia Hills: Changed conditions in the 19th and 20th centuries. In Layers of History: Essays on the Khasis-Jaintias, edited by David R. S, 37- 46. New Delhi: Regency Publication.

Laloo, S. T. (2025). Forgotten Catastrophe: The Khasi Hills and the Partition of 1947.

Yule, S. H. (1844). Notes on the Kasia Hills and people. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal XIII: 612-631.